Regina Krahl 康蕊君

Complete Essay

This blue porcelain bowl represents a historically significant discovery. After decades of controlled excavations in China and abroad and intense scrutiny of museum and private collections worldwide by a large pool of specialists, the history of Chinese ceramics is fairly well established today. We no longer expect an unknown type of imperial porcelain to turn up that had not been seen or recorded before. The present bowl marks such an occasion. With its sparkling sapphire-blue glaze and distinct design of five-clawed dragons – unquestionably a product of the Yuan dynasty (1271–1368) for the imperial court – it appears to be unique and adds a new facet to the historical record. It inhabits a singular spot in the evolution of imperial production at the Jingdezhen kilns in Jiangxi province. It is the only porcelain vessel glazed in monochrome cobalt-blue – or any colour – definitely made for the Yuan imperial house that appears to have survived. It is one of the earliest porcelains in this colour and one of the earliest decorated with the imperial dragon design. Since only a handful of imperial porcelains are preserved from this period – the others all being white – it can be considered the most important piece of Yuan imperial porcelain. It is an iconic artefact that stands at the beginning of the long history of China’s imperial porcelain production, documenting the Mongol emperors’ adoption, adaptation and instrumentation of Chinese luxuries.

Apart from its historic importance, it is also a most powerfully executed and strikingly beautiful work of art. It is superbly potted, the wide-open vessel with its generous, bulging profile elegantly balanced on a very narrow foot with characteristic, neatly trimmed foot ring that gives it a majestic poise, almost as if floating slightly above the ground. The relief decoration inside distinctly stands out, raised in lines of white slip, forming a subtle contrast to the overall blue glaze. The two dragons chasing each other around the inner sides, one with mouth open, the other with mouth closed, have long horns, bushy manes, and undulating bodies with scales indicated by fine cross-hatching, their spines emitting a row of flames, quickly rendered as if flickering, their legs terminating in five-clawed feet. The glaze retains its pristine gloss and is of a most satisfactory, deep, vivid blue, which would have required the best cobalt pigment that could be obtained, probably the costly metal high in iron and low in manganese that was imported from Iran ①.

The five-clawed dragon motif is so firmly associated with imperial artefacts of the Ming (1368–1644) and Qing (1644–1911) dynasties that it is often overlooked that it was in fact the Mongol emperors who made it a symbol of imperial privilege. Dragons in general are a very ancient Chinese motif and according to Patricia Ebrey were associated with the emperor already in the Han dynasty (206 BC – AD 220), but for centuries were not exclusively imperial. Because of their far-reaching auspicious associations, for example, as mounts of immortals and as water guardians, they became very popular and ubiquitous ornaments in Chinese art and architecture. Despite this wide distribution of the motif – or perhaps exactly because of its broad popularity – Emperor Huizong (r. 1100–1125) of the Song (960–1279) attempted to claim the dragon as an imperial symbol for himself, and endeavoured to prohibit its usage, for example as a textile design for commoners ②. Dragon motifs were prominent in and around the Song palaces and at the Song imperial tombs, but almost without exception, Song imperial dragons were three-clawed. Five-clawed dragons had occasionally been depicted side-by-side with three- and four-clawed creatures, but prior to the Yuan they were extremely rare and the number of claws does not seem to have carried any symbolic significance, certainly not as imperial insignia ③.

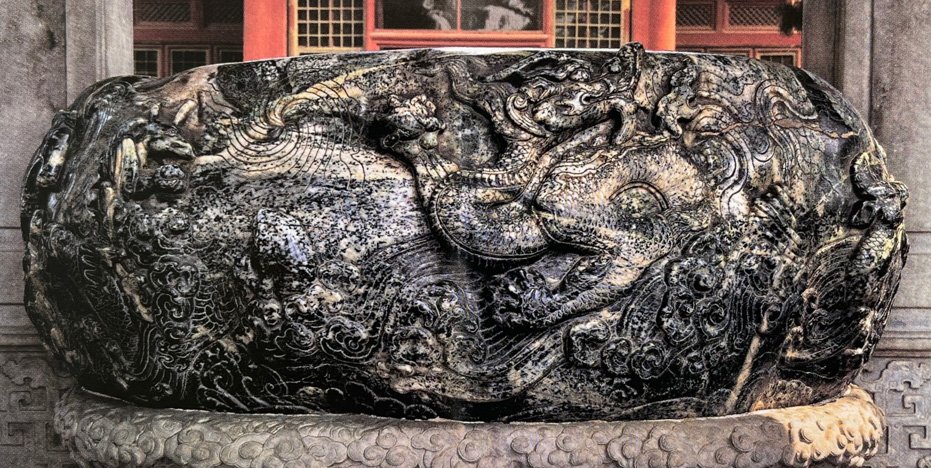

Very different is the story with the Mongol emperors, beginning with the Yuan founder Khubilai Khan (r. 1271–94). The Mongol emperors emphatically promoted the imperial association with five-clawed dragons. Perhaps the most remarkable artefact commissioned by a Mongol Khan to feature the dragon with five-claws, and one of the earliest, predating even the establishment of the Yuan dynasty, is the ‘wine bowl’, 70 cm high and 135 cm in diameter, carved from a single block of black jade or jade-like stone to the orders of Khubilai Khan (fig. 1). In 1265 it was placed in front of the Guanghan Hall, an important reception hall of the Mongol capital Dadu that was already in use before the new capital was inaugurated and the main palaces had been completed. The massive vessel is still standing in Beijing today, in Beihai Park ④.

–

① The similarity in composition of cobalt colourants used on Yuan porcelain and on contemporary Persian pottery suggests a cobalt origin from mines at Qamsar near Kashan, see Kerr & Wood 2004, pp. 675-7.

② Ebrey 2011, particularly p. 42 and p. 52.

③ Kessler 2012, p. 378 and passim, proclaims that the two-horned, five-clawed dragon design was an imperial emblem of the Song dynasty. However, none of the few Song (or Jin, 1115-1234) examples that can be found corroborate this. A five-clawed dragon is said to appear on one of the octagonal pillars in front of Emperor Yingzong’s (r. 1063–7) mausoleum in Gongxian, Henan (illustrated only in an old line drawing in Bei Song 1997, p. 179, fig. 157), but the main dragons on this pillar are three-clawed (ibid., pp. 176-8, figs 154-6). Pre-Yuan dates (but no imperial attributions) have been suggested for a small number of silk fabrics with five-clawed dragons (New York 2010, figs 258 and 265; Taipei 2001, no. IV-77; Krahl 1997, fig. 7), but these are now mostly attributed to the Yuan (e.g. Liu Keyan 2018, col. pls 3-8, 3-10 and 3-11, and pp. 25-30; Zhao Feng 2019, p. 15); one Ding dish with five-clawed dragon, of unusually large size and exceptionally coarse workmanship, can hardly be considered Song imperial ware (Taipei, 1987, no. 80); ditto for a Cizhou vase with five-clawed dragon, inscribed with the maker’s name (Indianapolis 1980, pl. 42).

④ New York 2010, fig. 59.

Black jade ‘wine bowl’, c. 1265, Beihai Park, Beijing. After: New York 2010, fig. 59.

Stone post from Yuan Shangdu, Inner Mongolia. After: New York 2010, fig. 101

(turned sideways for better legibility).

Little is remaining of Mongol palaces, but a carved stone post, over two metres tall, that formed part of a palace hall at the Yuan upper capital, Shangdu, today in Inner Mongolia, is testimony to their magnificence (fig. 2). Nancy Shatzman Steinhardt writes about its architecture: “Decorative components similar to this one, with five-claw dragons and floral motifs, were set into the corners of pillars, gates, and buildings to proclaim imperial grandeur. ⑤” Similar five-clawed dragons were found Ilkhanid dynasty (1258–1353), which ruled in parallel with the Yuan in Iran ⑥.

For their own attire, the Mongol emperors introduced five-clawed ‘dragon robes’ and wore matching jade belt plaques ⑦. Khubilai Khan is depicted hunting in a red five-clawed dragon robe under an ermine coat in a painting by Liu Guandao datable to 1280 ⑧. Emperor Tugh Temür, great-grandson of Khubilai Khan, known in China by his temple name Wenzong (r. 1328–32), had himself portrayed wearing such a robe on a magnificent silk tapestry mandala that he commissioned, now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, that can be dated between 1330 and 1332 (figs 3 and 4) ⑨. Wenzong himself and his elder brother Khoshila, who also briefly ruled as emperor, temple name Mingzong (r. 1329), and both their wives are depicted in the tapestry as donors, the brothers wearing a white and a blue sleeve-less coat, respectively, over a red long-sleeved garment, the two wives dressed in a brownish red. All their clothes are decorated with white five-clawed dragons, conspicuously set in scene to identify the sitters as the imperial family.

Imperial edicts prohibited non-imperial use of the two-horned five-clawed dragon design on textiles as well as vessels, as recorded in historical texts such as the Yuan shi [History of the Yuan], Yuan dianzhang [Statutes of the Yuan], Tongzhi tiao ge [The usual code] and other texts ⑩. Indeed, five-clawed dragons seem to be the only definite identifying feature of items connected to the Yuan innermost imperial court. Although these prohibitions were obviously not easy to enforce, there is doubt that artefacts from official workshops carrying this design were intended solely for the court. This is all the more significant since extremely few Yuan imperial works of art of any medium appear to have been excavated or handed down, so that this important near-century in the imperial history of China is today severely underrepresented in museums, including the imperial collections in Beijing and Taipei ⑪.

–

⑤ New York 2010, p. 73 and fig. 101.

⑥ Naumann 1977.

⑦ Zhao Feng 2019; and Taipei 2001, no. IV-8.

⑧ Taipei 2001, no. 1-5; and Liu Keyan 2018, col. pl. and fig. 3-18, with drawings of the type of robe he is wearing, figs 3-19 and 3-20.

⑨ New York 1997, no. 25; New York 2002, figs 125 and 126; and New York 2010, p. 113.

⑩ Zhao Feng 2019, p. 21; Lam 2012, pp. 41-2; Lam 2019, p. 35.

⑪ No Yuan imperial tombs have been excavated. According to Kwanten 1979, p. 124, “It was a Mongol tradition to hide the burial place of their ruler. The ground was trampled, and trees were planted on it until the place could no longer be distinguished from the surrounding countryside; moreover, those actually involved in the burial were executed, so that within a relatively short time, the precise location of the burial place was forgotten.”

Emperors Wenzong and Mingzong and their wives depicted as donors, details of the

mandala in fig. 4, 1330-1332, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. After: New York 2010, p. 113.

White and blue were colours the Mongol imperial clan held in high regard, as is reflected in the choice – undoubtedly not fortuitous – of the two emperors’ coats in their woven representations as practising Buddhists. Both were considered auspicious colours and had ritual significance, being associated in particular with ancestral worship. ‘Sacrificial blue’ was – like elsewhere – auspicious as the colour of the sky and its use was restricted by the court ⑫. One of the main Mongol deities deriving from traditional shamanistic folk religion was Köke Möngke Tenri, the Blue Eternal God, offerings to whom were reputedly made in blue vessels. Blue was also a favourite colour to depict Buddhist deities in painted and woven mandalas, or thangkas, like the Metropolitan Museum piece, where a blue-skinned Yamantaka, or Vajrabhairava, represents the focus of the Yuan emperors’ devotion (fig. 4). Watt and Wardwell state “that these portraits and mandalas were meant to be housed or displayed in the imperial ancestral halls and portrait halls (yingtang) for emperors and their consorts that were in temples connected with the imperial family” ⑬.For offerings in these halls, porcelain receptacles were used.

–

⑫ Kessler 2012, p. 374, quoting an article by Yi You of 1982.

⑬ New York 1997, p. 98.

Vajrabhairava mandala, silk tapestry, c. 1330-1332, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York., Purchase, Lila Acheson Wallace Gift, accession no. 1992.54

It is recorded that the Mongols established a special office, the ‘Fouliang Porcelain Bureau’ (Fouliang ciju) – Fouliang referring to the region of Jingdezhen – already in 1278, before their final conquest of the capital of the Song, which suggests an early imperial interest in its porcelains. For much of the Yuan dynasty, however, the mission of this office seems to have been rather limited. According to Liu Xinyuan, who excavated imperial porcelains in Jingdezhen, the Yuan imperial kilns vanished virtually without a trace from the gazetteers of the county, prefecture and province, where they had existed ⑭. However, he found a reference, apparently the only one connecting the Yuan Porcelain Bureau in Jingdezhen to an emperor, that in 1331 Emperor Wenzong appointed an official named Du Run to oversee the porcelain production ⑮. Even if we do not know whether Du ever actively filled this post and what may have been produced under his auspices, it documents Wenzong’s interest in the production of the kilns.

Emperor Wenzong was a highly cultured ruler, who had studied the Confucian classical texts, commissioned the publication of an encyclopaedia, composed poetry, practised calligraphy and painting, and founded the Kuizhangge Academy, an institution to propagate Chinese culture, where his large collection of paintings, calligraphies and books was housed. His name comes up time and again in connection with Yuan imperial porcelain and, as we shall see, there are good reasons to attribute the present bowl also to his reign period.

Not only historical documents are missing that could enlighten us about the Fouliang Porcelain Bureau’s activities; of the wares themselves that were made for the Yuan court exceedingly few remain. Although we don’t know how much was lost in the intervening centuries, it seems that little was produced altogether. Unlike the emperors of the Ming and Qing dynasties, the Yuan rulers do not appear to have commissioned porcelains for the multifarious necessities to furnish a palace household. Rather, they appear to have ordered porcelains only sporadically and for special purposes. For eating utensils and other vessels of daily use the Mongol emperors most probably preferred gold and other precious materials; but the fact that porcelain could be created in colours of ritual significance may well have made it their preferred medium for sacrificial purposes.

–

⑭ Liu Xinyuan 1998, p. 6.

⑮ Liu Xinyuan 2001; according to Kessler 2012, p. 482, Ts’ai Mei-fen names another official, Duan Tinggui as Du’s predecessor, but Peter Lam lists him as having been active later, in the Hongwu period (Lam 2019b, vol. 1, p. 44).

Yuan imperial blue porcelain: the present bowl. (19.6 cm width, 8.7 cm height, 5.5 cm foot dia.)

As a single witness to Yuan imperial blue porcelain, the present bowl has no direct match, but it fits like a missing link into the picture we can form today of the activities at the Jingdezhen porcelain workshops in the fourteenth century, and perhaps the ritual practices at the Yuan court (fig. 5). It relates closely to the only other type of Yuan imperial porcelain of which complete vessels are preserved: white wares.

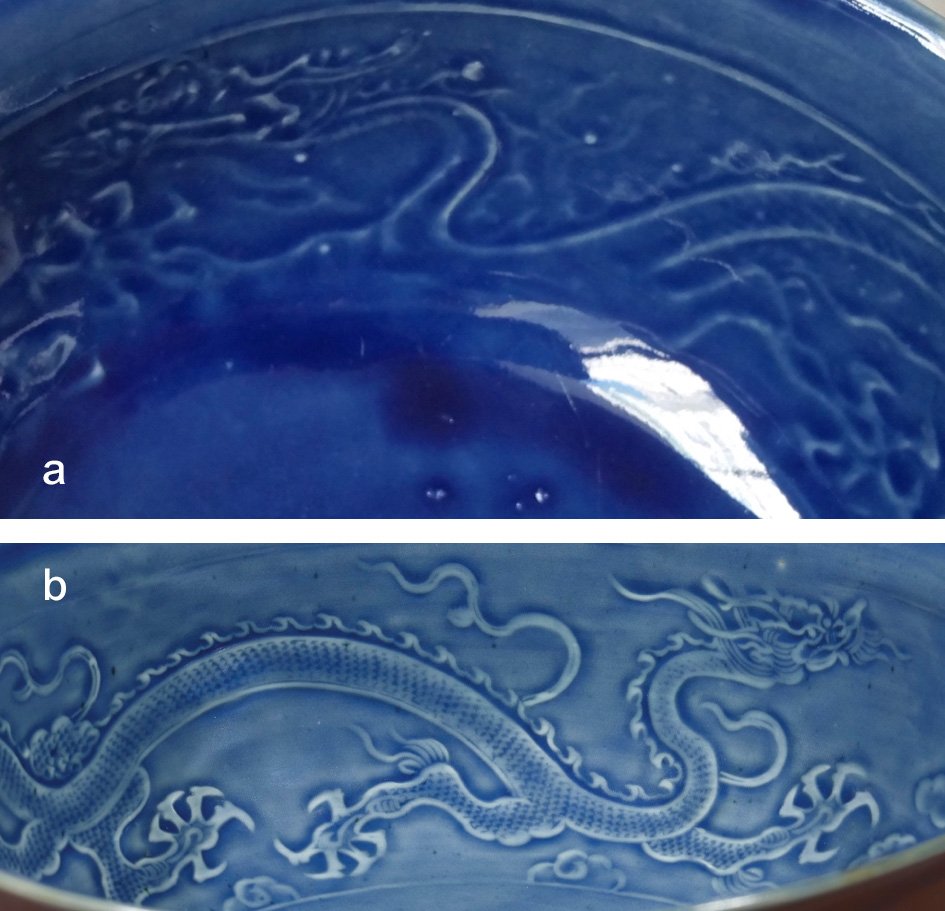

The dragon design on the present bowl is created through a technique that is known by the term anhua, ‘hidden decoration’. In the present case this would be an inappropriate description, since the design is clear to see; but typically, anhua was used in white on white, under a neutral, opaque ‘egg-white’ (luan bai) glaze and remains then indeed often virtually hidden unless the vessel is held against the light, where it can show as a shadowy silhouette. The technique used to create anhua is still not fully understood, but seems to involve a white slip coating of the porcelain body into which a mould with incised decoration was impressed to create a low-relief pattern on the vessel, which was then covered with glaze. On the present bowl, the outlines of the dragons are so strong and freely executed that the moulded pattern may have been emphasized by hand with trailed lines of slip.

White porcelains with anhua may have been used in various official contexts under the Mongols ⑯, but only a small number was made for imperial use and decorated with five-clawed dragons. Some bear in addition an inscription that provides useful information about their usage and dating. In the early 1960s, Sun Yingzhou, renowned collector and porcelain specialist, who worked at the Palace Museum and later donated his large ceramic collection to it, discovered in Beijing three important white dishes decorated with five-clawed dragons, lotuses and the bajixiang, and impressed with the characters taixi ⑰. The inscription refers to the Taixi zongyin yuan, the Office of Imperial Ancestral Worship, which supervised ancestor ceremonies for the Mongol emperors and was in charge of imperial offerings to ancestral portraits. It was set up under Emperor Wenzong in the first year of the Tianli reign, 1328, and existed until 1340. The dishes therefore would have been ordered either by Wenzong himself or his immediate successor to be used in a yingtang, the same kind of imperial temple hall for which Wenzong had commissioned the mandala depicting himself and his brother (fig. 4). Of the three dishes, one is now preserved in the Palace Museum, Beijing; one is in Beijing University; the whereabouts of the third are unknown, but one dish of this type found its way into the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, from the J.G. Maxwell Brownjohn bequest (fig. 6a) ⑱.

Besides these dishes, a white bowl (fig. 6b) and several stem bowls (fig. 6c) are recorded, which are very similar in overall quality and style, equally decorated with five-clawed dragons, but not inscribed. The bowl is of the same size as the present piece and looks like its white counterpart. It was found in Huocheng, Xinjiang, known as Almaliq, an important seat of descendants of the Mongol ruling clan. Stem bowls were typically used in Tibetan Buddhist ritual ceremonies, and examples with five-clawed dragons were recovered from several hoards and tombs connected to important Yuan personalities, probably representing imperial gifts ⑲.

–

⑯ White porcelains inscribed shufu, for example, were made for the Bureau of Military Affairs.

⑰ Sun Yingzhou 1963.

⑱ See Zhongguo taoci quanji 2000, pl. 104 for the Palace Museum dish, pl. 99 for the Victoria & Albert Museum piece (acquisition no. C.49-1965).

⑲ For the bowl see Peng Qingyun 1993, no. 599; for a stem bowl now in the Gaoan Municipal Museum see Liu Jincheng 2006, p. 86; for one from the family tombs of painter and official Ren Renfa, now in the Shanghai Museum, see Peng Qingyun 1993, no. 601. Further stem bowls reputedly with five-clawed dragons are said to have been excavated, for example, from a tomb near Jingdezhen; from hoards in Hangzhou, Zhejiang; in Shexian, Anhui; in Dayingzi, Inner Mongolia; in Shunyi, Beijing, etc. Images, however, are generally not good enough and descriptions in different publications contradictory, so that it is not always possible to verify the number of claws on these vessels. Fragmentary pieces are recorded from Hutian and Luomaqiao kiln sites at Jingdezhen, see Jingdezhen Hutian 2007, vol. 1, fig. 278 and vol. 2, col. pl. 153: 1 centre, 2, 3, and 4 right, and Weng and Li 2021, p. 89. An unusual qingbai stem bowl with five-clawed dragons, different in type from the ‘egg-white’ pieces above, is illustrated in Wood 1999, p. 57.

a) Dish marked taixi, Victoria & Albert Museum, London. After: Zhongguo taoci quanji 2000, pl. 99.

b) Bowl, from Huocheng, Xinjiang. After: Peng Qingyun 1993, no. 599.

c) Stem bowl, from a hoard in Gaoan, Jiangxi. After: Zhongguo taoci quanji 2000, pl. 116.

d) Dish marked Tianshun nian zao, Sir Percival David Collection. After: Krahl & Harrison-Hall 2009, fig. 5.

Such vessels would have been perfect to accompany the white dishes in imperial rituals.

Another white porcelain piece with claims to a Mongol imperial connection is an ‘egg-white’ anhua dish decorated with phoenixes instead of dragons, traditional symbol of the empress. Preserved in the Sir Percival David Collection in the British Museum, it includes in its moulded decoration the inscription Tianshun nian zao, ‘made in the Tianshun period’, foreshadowing Ming imperial reign marks (fig. 6d) ⑳. Tianshun refers to the two-months reign of the infant Mongol ruler Aragibag (Alajiba) in 1328, who was installed as emperor in the upper capital, Shangdu, while Wenzong ascended the throne in the main capital, Dadu (Beijing). Although it is considered unlikely that his reign period would have been long enough for the piece to be commissioned and completed in far-away Jingdezhen, loyalist factions continued to fight for Aragibag, who was reported to be missing, throughout Emperor Wenzong’s reign. Since he inherited the throne as an infant (he was born in 1320), the female imperial symbol of phoenixes on this dish probably refers to the empress dowager.

These few monochrome white pieces represent the only Yuan imperial wares known to have survived besides the present blue bowl. They can be dated to Emperor Wenzong’s brief reign or the years immediately around it and suggest that imperial porcelains were made for the Yuan court for only a very short period. They were made for ritual functions performed by the emperor.

The overall similarity of the present bowl to these white imperial porcelains is so obvious that it has to be contemporary and must have served a similar purpose. Since we have no indication that the Yuan emperors ever commissioned Jingdezhen porcelains for eating or drinking, and since the blue colour had ritual significance for the Mongols, we can assume that this bowl was equally used for ceremonial offerings, in a sacrificial ceremony in one of the yingtang. Seated in a yingtang in front of a mandala like the Metropolitan Museum one (fig. 4), the two emperors are likely to have worn garments similar to those depicted in their portraits and to have used matching porcelain vessels in white and in blue decorated with white five-clawed dragons for the offerings they made (fig. 7).

–

⑳ Krahl & Harrison-Hall 2009, p. 14, fig. 5 (PDF A409).

a) Miniature tripod jue from Shexian hoard, Anhui, After: Zhongguo taoci quanji 2000, pl. 243.

b) Cup with prunus design, from Baoding hoard, Hebei. After: Zhongguo taoci quanji 2000, pl. 244.

c) Handled cup and dish, National Palace Museum. After: Taipei 2001, p. 154.

A few other monochrome blue vessels can be attributed to the Yuan dynasty, but not to the imperial house. They were mostly decorated in gilding and probably represented luxury wares for an affluent elite. It is recorded both in Korean documents as well as in the Yuan dianzhang (Statutes of the Yuan dynasty), published during the reign of emperor Yingzong (r. 1322-23), that Kublilai Khan, after having been presented by a Korean envoy with a gold-decorated vase, was not at all pleased about the extravagance and decreed that no ceramics should be decorated with gold ㉑. Tripod vessels in the form of archaic bronze jue decorated, for example, with prunus and moon, might have been used in Confucian rituals, but not in an imperial context. The Mongol emperors did generally not perform Confucian rituals themselves, and the tripods are miniatures (fig. 8a) ㉒. Receptacles for food and drink include prunus-decorated cups, one with flared rim (fig. 8b), one with handle (fig. 8c); a dish (fig. 8c); a spouted bowl with cloud motifs; and a pear-shaped bottle decorated with dragons ㉓. None of the dragons are of the imperial five-clawed variety and there is no other indication that the emperors would have used these blue vessels. Fragments of very similar pieces were discovered at the Luomaqiao kilns of Jingdezhen ㉔. The same is true for another group of Yuan blue-glazed porcelains, decorated with white reserves of three-clawed dragons and other motifs, some of which were even exported and can be traced, for example, to Turkey, Iran and Korea ㉕.

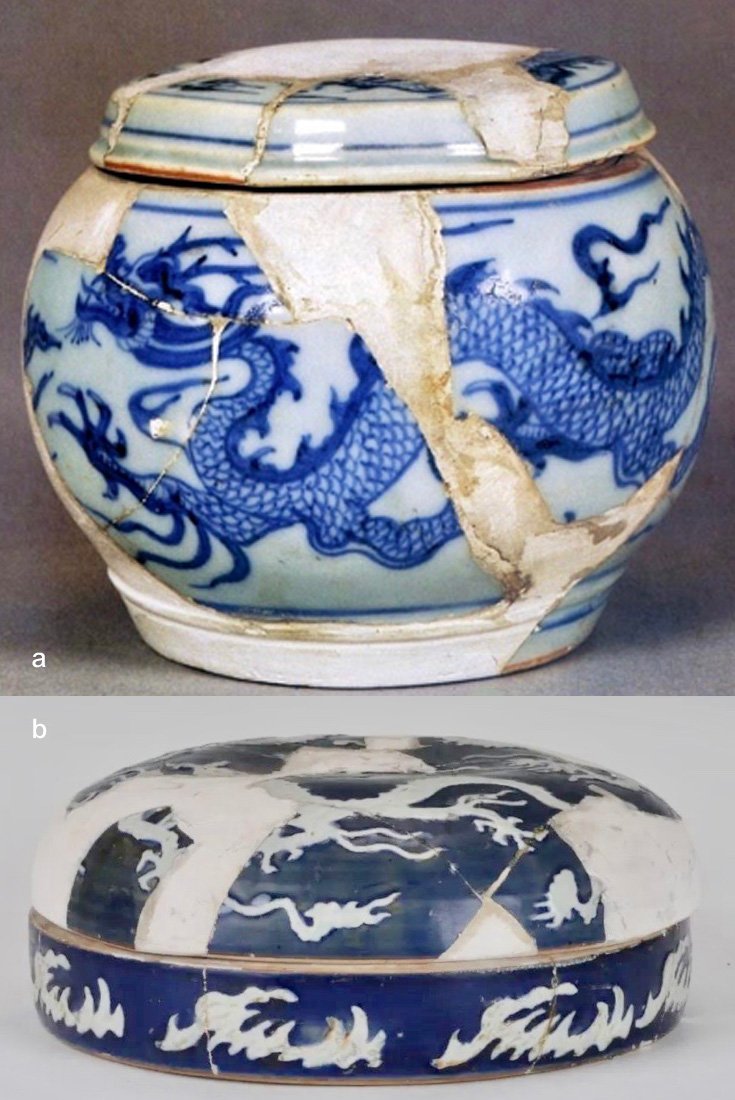

Besides the present blue imperial bowl and the few white imperial pieces that are extant, Yuan imperial porcelains are known only from examples deliberately destroyed and buried at the kiln site before they could have been delivered to the palace. A few such vessels with five-clawed dragons, recovered from what is believed to have been waste heaps of the Yuan imperial kilns at Doufulong, Zhushan in Jingdezhen, have been reconstructed from incomplete sherds. They include examples painted in cobalt blue under a transparent glaze (fig. 9a); in blue under or in gilt over a turquoise glaze; and decorated in white relief against a blue glaze (fig. 9b) ㉖. No complete pieces of these types are known to be preserved ㉗. Plain blue-glazed sherds have also been reported from the site, but do not seem to have been published. The range of shapes is extremely small, consisting largely of chess-piece jars and ink-stone boxes.

Studying the dragons on the Zhushan pieces, Liang Sui states that they have small scales and are lacking the ribbed band under the belly, they have hair at the back of the head, only few hairs, or strands of hair, at elbows and knees, and the claws are arranged in one curved line, all very different from the dragons of the type seen on the non-imperial ‘David Vases’ of 1351, but closely related to the present bowl ㉘. He points out the stylistic similarity to the taixi-marked dishes, which can be attributed to the period 1328–40, and concludes that they equally predate the ‘David Vases’.

–

㉑ Gompertz 1956, p. 401; Gardellin 2019, p. 14.

㉒ They came from hoards in Hangzhou, Zhejiang, and Shexian, Anhui, see Ye Peilan 1998, pls 202 and 203.

㉓ The flared cup and spouted bowl come from the Baoding hoard, Hebei; see Ye Peilan 1998, pls 200 and 201; the handled cup and dish are in the National Palace Museum, see Taipei 2001, nos IV-55 and 56; for the pear-shaped bottle see Christie’s Hong Kong, 28th November 2018, lot 2903.

㉔ Weng & Li 2021, pls 7, 41, 42.

㉕ Krahl 2014; Chopard, Déléry & Gardellin 2020; Lee 2015, p. 18; and Weng & Li 2021, pls 4, 5, 11, 42.

㉖ Liu Xinyuan 1993; Beijing 1999, nos 1-8; Beijing, 2009, pp. 58-9, 144-5; and Huang Yunpeng 2006, p. 275, fig. 3.

㉗ A blue-and-white bowl decorated with five-clawed dragons seems to have made it to a building believed to have been in charge of administering and storing Yuan imperial wares, as a sherd excavated at Luomaqiao in Jingdezhen suggests; see Weng & Li 2021, figs 3.2.24 and 3.2a.2.

㉘ Beijing 1999, pp. 14f.; for the ‘David Vases’ see Lam 2009 and 2019a.

a) Underglaze-blue painted chess-piece jar, from Zhushan, Jingdezhen. After: Shanghai Museum 2012, pl. 83.

b) White on blue decorated ink-stone box, from Zhushan, Jingdezhen. After: Beijing 1999, pl. 7.

Liu Xinyuan has strongly argued that this group of imperial wares was intended for the Wenzong Emperor, pointing out that he was the only Yuan ruler who is likely to have required chess-piece jars and large ink stones, since he was the only imperial chess player and fond of doing large-scale calligraphy, which, carved in stone, could be distributed among his officials in form of ink rubbings ㉙. Since the pieces discovered are stylistically very consistent and to ninety percent decorated with five-clawed dragons, it is likely that they were made within a short span of time, and conceivable that they represent a single imperial order. While the Wenzong Emperor’s premature death aged twenty-eight, after only some three years on the throne, should not have precluded the commission of such pieces, it might well have prevented their timely delivery to Beijing and may instead have resulted in their destruction right at the kilns. This view has been challenged by some scholars who attribute these pieces to the very end of the Yuan period ㉚. Whatever their date may be, these fragments represent the only other possible remnants of Yuan imperial porcelain.

–

㉙ E.g. Liu Xinyuan 1993, p. 36; Liu Xinyuan in Osaka 1995, pp. 164-6; Liu Xinyuan 2001; and elsewhere.

㉚ See Lam 2015, pp. 201ff. and 211f.; Lam 2019a, pp. 26 and 37f.; and Ma Wenkuan 2005. Ma, however, discusses mainly Yuan wares sent abroad, which Liu also attributed to Wenzong’s reign, although they differ in style from the pieces excavated from the reputed imperial workshop site and are more likely to come from private kilns.

a) Red-and-blue bowl, Private Collection. After: Sotheby’s London, 6th July 1976, lot 131.

b) Blue-and-brown bowl, Private Collection. After: Sotheby’s Hong Kong, 9th October 2020, lot 46.

c) Blue-and-brown dish, The British Museum. After: Harrison-Hall 2001, no. 1-21.

d) Blue-and-brown sherd, from the early Ming palace site, Nanjing. After: Hong Kong 1996, no. 26.

Both the monochrome-glazed and the underglaze-blue decorated imperial wares, however, served as direct blue-prints for early Ming pieces, which therefore are sometimes confused with their Yuan predecessors. There is a small group of bi-chrome and monochrome-glazed porcelains with anhua five-clawed dragons, superficially quite similar to the present bowl, but very different when compared more closely. It includes bowls glazed in red and blue (fig. 10a) and in brown and white; bowls, dishes and stem bowls in blue and brown (figs 10 b-d); and bowls and dishes in monochrome red ㉛. A blue-and-brown rim fragment of this type was

recovered from the moat around the Hongwu Emperor’s (r. 1368–98) palace in Nanjing (fig. 10d), and a fragmentary red bowl was excavated from the Hongwu stratum of the Jingdezhen imperial kiln site ㉜.

Although these colour-glazed pieces are closely modelled on the Yuan style exemplified by the bowl discussed here, a direct comparison immediately shows that they differ in virtually every aspect (fig. 11). With its generous, rounded body raised on a narrow foot, the present bowl has a most sophisticated form that would have been difficult to fire without accident. Proportions were therefore modified later on, the foot made wider, resulting in a more earthbound profile. The Yuan glaze is very glossy and the cobalt blue has yielded an intense and brilliant colour. The Ming version shows the weak, watery tone that is characteristic also of Hongwu blue-and-white, as due to restrictions on international trade, imported cobalt had become scarce. This may also be the reason that blue here was generally used for only one side of the vessel and that – again like with underglaze-painted porcelains – copper-red examples are more numerous than ones using cobalt-blue.

The dragon design on this Yuan bowl is very lively and has a hand-finished quality; the Ming version has become rather rigid, noticeable particularly on the flames down the dragons’ spine. How important five-clawed dragon feet were to the Yuan emperors is reflected in their outsized rendering on the present blue bowl. To sum up, one can say that the colour-glazed pieces made for the Ming emperor are completely lacking the dramatic quality and the striking presence of this Yuan bowl – defining characteristics of works of art made under Yuan rule in general. The same is true for a small group of Hongwu blue-and-white pieces with five-clawed dragons based on Yuan prototypes (such as fig. 9a), but painted in a much weaker, more formal style in an insubstantial cobalt colour ㉝.

That a Yuan date is sometimes claimed also for these later versions (as in fig. 10) has its reasons. It is universally agreed that production at Jingdezhen under Mongol rule must have ended around 1352, when the region was for several years fought over by Red Turban troops and from then on seems to have been lost for the Yuan. The Mongol court would certainly not have been able to restart official porcelain production thereafter. The region came under the control of Zhu Yuanzhang (1328-98), the later Hongwu Emperor, who fought together with Red Turban rebels. In 1356, he installed himself in Nanjing, Jiangsu province, and proclaimed himself Duke, and in 1364 Prince (or King, wang), of the State of Wu, before declaring himself Emperor of the Ming dynasty in 1368.

His military power may have calmed the region sufficiently for production at Jingdezhen to have re-started at the very end of the Yuan, but not to Mongol orders. Wishing to become emperor, Zhu Yuanzhang himself might well have taken advantage of his exclusive access to the porcelain manufactories and have commissioned ‘imperial’ porcelains with five-clawed dragons for himself, as if he were emperor already. The usurpation of the five-clawed dragon motif associated with Mongol imperial power might even have been of symbolic relevance to him.

The kilns could have been re-opening in the last decade of the Yuan, working to the orders of the Prince of Wu, and continuing to work for him without much interruption when he had become Emperor, i.e. from the late 1350s to 1370s. This change of patron after the demise of the Yuan and the very different political situation led, however, to a distinct change of style in Jingdezhen porcelain, creating what Peter Lam referred to as ‘Wu-state style’ ㉞.

These differences, which clearly set off imperial wares made for the court of the Yuan from the Ming or pre-dynastic Ming wares made for the court of the Hongwu Emperor or the Prince of Wu, were probably circumstantial rather than intentional. There is, however, one other distinction, which may have been deliberate: while the dragons on the present blue bowl are running to the left, on the colour-glazed vessels made for the Ming ruler they are facing right – which may be accidental, or else a very literal change of direction (fig. 12).

–

㉛ For the red-and-blue bowl, formerly in the collection of Sir Percival and Lady David, later the Idemitsu Museum of Arts, Tokyo, see Idemitsu Bijutsukan 1981, no. 765; for the brown-and-white bowl in the Yamato Bunkakan, Nara, see Nara 1977, no. 114; for a blue-and-brown bowl see Sotheby’s Hong Kong, 9th October 2020, lot 46; for a blue-and-brown stem bowl from the Sedgwick collection and a dish from the Eumorfopoulos collection, both in the British Museum, see Harrison-Hall 2001, no. 1:20 and 21; red-glazed bowls and dishes are in many museum collections, e.g. in the British Museum, see Harrison-Hall 2001, nos 2: 3 and 4. The authenticity of a monochrome blue-glazed bowl, sold at Poly International Auction Co., Beijing, 9th December 2018, lot 5621, could not be independently verified; a blue-glazed dish with four-clawed dragons is in the Bristol City Art Gallery, no. N7881.

㉜ For the blue-and-brown sherd see Hong Kong 1996, no. 26; for the red bowl fragment, Taipei 1996, no. 15.

㉝ For a direct comparison see Lam 2019a, p. 32, figs 19 and 21.

㉞ Lam 2015, pp. 202f. and 212f. The blue-and-white pieces with painted and sometimes also with anhua five-clawed dragons include, for example, a bowl in the Tianminlou collection (Lam 2015, p. 203, fig. 23; and Lam 2019a, p. 32, figs 21 and 22); a dish from the Clark collection (Garner 1954, pl. 2C); one from the Rui Tang collection (Sotheby’s London, 5th December 1995, lot 382); further dishes (Christie’s Hong Kong, 5th/6th November 1997, lot 1032; and 29th May 2007, lot 1450); meiping vases inscribed chun shou, probably a brand of wine, such as one in the Shanghai Museum (Wang Qingzheng 1987, col. pl. 33); or a large pear-shaped vase, yuhuchunping, excavated from a princely Ming tomb in Xingyang city, Henan (Zhang Bai 2008, vol. 12, pl. 235). This type also came to light in the moat around the early Ming imperial palace in Nanjing (Hong Kong 1996, nos 23 and 24).

a) The present bowl, Yuan dynasty (Note the elegant aesthetic wide stance, small and short flaired foot, and deep blue color)

b) Bowl, early Ming dynasty, after Sotheby’s Hong Kong, 9th October 2020, lot 46 (deep bowl form; wide, tall and straight foot, light grey blue color)

a) Dragon moving left, detail from the present bowl, Yuan dynasty.

b) Dragon moving right, detail from blue-and-brown bowl, early Ming dynasty. After: Sotheby’s Hong Kong, 9th October 2020, lot 46.

The unglazed base exposes the fine creamy white clay. Iron spots on the surface of the foot ring burnt brown in the firing. The neatly hand-trimmed foot rim reveals a double-slant-cut foot. The nipple-like protrusion in the middle of the elevated center is a potting remnant particular to ceramics from the Yuan period. These traits combined, along with the monochrome blue glaze, assist in dating the porcelain to the 2nd quarter of the 14th c.

The Yuan dynasty marks a dramatic turning point in the history of Chinese ceramics after the modest, softly coloured and unobtrusively decorated stonewares of the Song. Under the Mongols, potters established completely new production lines of porcelain that laid the ground and provided models for centuries of Ming and Qing imperial wares. Without the innovative energy at the Jingdezhen porcelain kilns during the Yuan dynasty, the history of China’s imperial porcelain production would certainly not have taken the direction it did. Emperor Wenzong may have been a driving force in this respect and the present bowl is a key specimen to document this process.

As the only monochrome blue imperial piece from the Yuan dynasty, it can claim to be the most important imperial porcelain vessel extant from this period. As a previously unknown porcelain type, it opens new insights into the Mongol emperors’ connection to and interest in Chinese ceramics. While they may not have been committed to commissioning porcelains for the imperial household, they may well have favoured the monochrome coloured wares of Jingdezhen as suitable for ceremonial activities, where colours were significant. To use in official contexts porcelains clearly signalling their authority became a tradition for the rulers of China. This blue bowl with its five-clawed dragons marks the beginning of this rite.